Phoenicid Meteor Shower Guide

The Phoenicids are a variable rate meteor shower occurring annually in late November and early December. Its name comes from the Phoenix constellation. This constellation, which is located in the far southern sky, is the point from which these meteors radiate.

Most years there are very few meteors per hour. Other years provide exciting outbursts, raining the firmament with significantly greater numbers of meteors.

The Phoenicid meteor shower originates from debris left behind by comet 289P/Blanpain. Best views are in places with very dark, stable atmospheric conditions and with minimal moonlight interference.

What is the Phoenicid Meteor Shower?

The Phoenicid meteor shower is one of the most rare and fascinating events to appear in the field of meteor astronomy. The shower is best known for its association with the elusive comet 289P/Blanpain. It connects history, science, and a bit of intrigue.

The Phoenicids were first observed in 1956 by Japanese scientists in Antarctica. They were dazzled by an intense show of meteors lighting up the southern sky. For decades afterwards, no one observed or recorded much, creating a chasm in observations until the shower reappeared in 2014. This unusuality is what makes each Phoenicid shower so special for amateur skywatchers and professional astronomers alike.

The Mystery of Its Parent Comet

Comet Blanpain aka D/1819 W1, which was lost to history after its first observed return in 1819. By the early 20th century, its activity had ceased, and it was considered to have disintegrated or just disappeared.

In 2003, astronomers detected a small body, 2003 WY25, on a trajectory consistent with Blanpain’s original orbit. This discovery indicated that the comet’s debris was indeed still present, generating a resurgence of interest in the Phoenicids.

The Phoenicid meteors we see today are the result of Comet Blanpain’s dusty trail. Every time a comet takes a close pass to the Sun, it releases particles of rock and ice. In Blanpain’s case, the detritus is largely minuscule—sometimes no larger than a piece of sand.

This dust trail floats in the wake of the comet, closely following its orbit. As Earth passes through this area, the Phoenicid particles strike the upper atmosphere. The ablation process—causing friction to heat and vaporize the particles—produces the bright streaks we experience as meteors.

Specifically, size and the chemical composition of each particle matter. Small, silicate-rich grains are more likely to burn up quickly, creating short, bright spikes. The denser or the fresher the dust trail is, the more visible meteors are spread throughout the year. A thinner or older trail can result in a more subdued meteor shower.

Locating the Phoenix Constellation Radiant

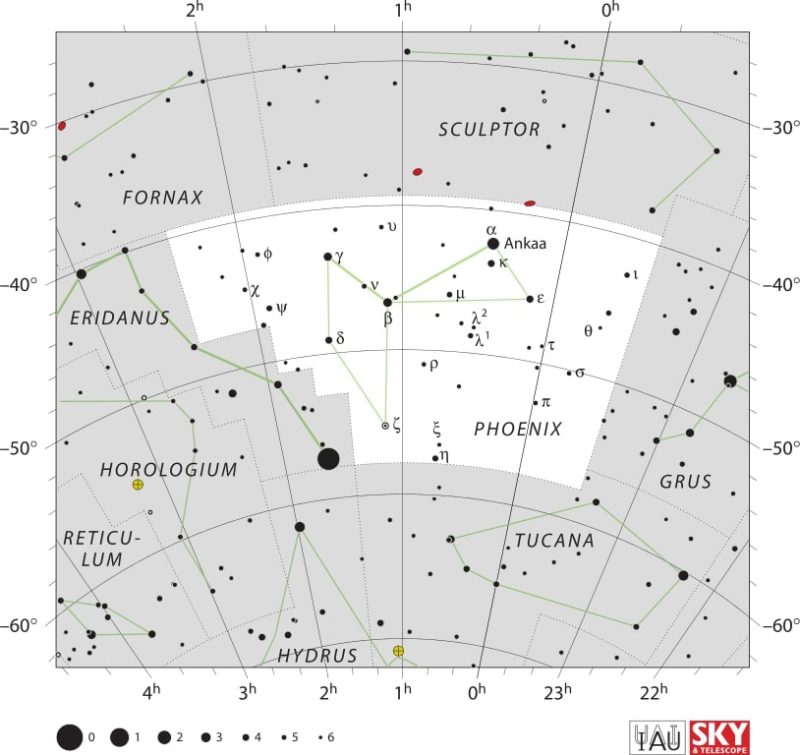

In order to observe the Phoenicid shower, it’s important to understand how and where to view it. The radiant—the place in the sky where all the meteors appear to originate—lies in the constellation of Phoenix.

This distinctive group of stars is located in the southern sky, beneath the more well known constellation of Aquarius.

To identify the radiant, you’ll be looking for a small, dim V-shaped grouping of stars in an area of the sky otherwise devoid of bright references. When the Phoenicids are likely to be most active in early December, the radiant will be highest in the sky near local midnight.

Identifying the radiant’s location helps distinguish Phoenicids from other showers and increases the chances of spotting more meteors.

Understanding Phoenicid Meteor Speed

Phoenicid meteors hit Earth’s atmosphere at relatively slow speeds—around 18 kilometers per second. This makes them quite a bit slower than the meteors from the Perseids or Leonids, for example.

Their slower speed makes Phoenicid meteors appear relatively soft and even more colorful with longer trails. On the whole, these meteors tend to show up more as long, flowing lines than quick darts.

This speed difference is what plays the largest role on the brightness and the type of trails observed, making Phoenicids distinct amongst showers.

Decoding the Zenith Hourly Rate

The Zenith Hourly Rate, or ZHR, indicates how many meteors an observer would see. Only during ideal conditions, with the radiant positioned directly overhead. For the Phoenicids, the ZHR can swing from single digits in quiet years to over 100, as seen in 1956.

This uncertainty makes the shower quite unpredictable. The ZHR is calculated by visually counting meteors and correcting for sky coverage and the position of the radiant.

The Phoenicids are much more variable than familiar meteor showers like the Geminids and Perseids. The rate is subject to variation from the dust trail movement or from variations in Earth’s trajectory through the debris.

Telling Phoenicids Apart From Others

Distinguishing Phoenicids from other showers requires some careful timing and radiant checks. Their activity peaks around early December and the radiant being in Phoenix does help confirm their identity.

Phoenicid meteors are generally slower and more steady, a yellowish color with very direct paths. Observers can tell Phoenicids apart from faster meteor showers such as the Geminids by watching for their direction and speed.

Viewing the Phoenicid Meteor Shower

The Phoenicids meteor shower surprises skywatchers every December. It’ll be one of the best shows around if you know when and where to look.

When to view the Phoenicids

The Phoenicids will be active between November 28 and December 9, with a peak on December 2. The Southern Hemisphere will enjoy the best viewing conditions due to an all-night radiant in the constellation Phoenix.

In the US and other Northern Hemisphere locations, viewing is possible but may require more planning due to the radiant’s lower position and brighter moonlight this year.

Moon Phase and Its Impact

A moon phase such as a full moon will cause bright moonlight to wash out skies, creating challenges for those trying to see the fainter meteors.

Look at lunar calendars and choose nights when the moon is lower in the sky or before it rises, or sets early. Less moonlight will result in superior viewing, so find a place that has as little artificial light as possible.

Weather Considerations

These winter-weather forecasts are notoriously difficult to pin down. Those who live in the Southwest and southern states are usually rewarded with clearer skies during December.

Gear Up for Meteor Gazing

Comfortable gear will make all the difference while meteor watching. With some simple preparation, you can experience it in a way that’s fun and easy!

A red flashlight is ideal for reading star charts in the dark. A retro notebook, paper or digital, is useful for recording your meteor tally or making notes. Star maps, either printed or through an app, assist you navigate along the night sky.

Lawn chairs or blankets would be great too, as they’ll allow for maximum comfort and viewing potential. Wear layers, even in the summertime, as nights can become quite chilly.

Have a plan for snacks, drinks, and bathroom breaks. If you’re out with kids, snacks and warm drinks are a great way to keep them happy and engaged.

My Take: Patience Pays Off

As you watch this rare Phoenicid meteor shower, you’ll experience a lesson in patience. You land in the midnight hour, your gaze immediately searching the heavens. This seemingly idle period is hardly time lost.

Sure, too much impatience ruins the entire evening—a premature departure and you’ve missed the show of a lifetime. If you hold out, the reward is clear: a flash of light that makes all the waiting worth it.

Patience is more than simply the absence of action. It’s delaying the temptation to throw in the towel too soon.

There’s no benefit to rushing things along. Most people do not like to wait, and being intolerant of the wait can be an impediment to dealing with larger issues in life. Waiting for the slow parts pays off, but it means that you’re prepared when the good stuff finally comes.

That’s the case with meteor showers and with life. One impulsive step can lead to disaster, though a little more forbearance goes a long way in preventing serious missteps.

The sheer pleasure of enjoying what a meteor shower has to offer increases every time you allow yourself to relax and simply immerse yourself in the experience. It’s more than just tallying meteors, though.

It’s not just about enjoying the refreshing breeze—though that certainly helps! Waiting for results can be difficult, but it’s an important lesson on how to deal with uncertainty.

After decades of waiting for meteor showers, I have come to appreciate that the most beautiful part is the calm before the universe ignites.

Conclusion

The Phoenicids may not grab the headlines like the Geminids or Perseids. They do provide a calm night and an opportunity to see some of the rarest sights that dot our skies. Many miss this shower because of low rates, but the quiet hunt can pay off with a few bright streaks. Come bundled in your coziest coat, relax, and give your eyes a moment to adjust. The sky has a special reward for those who come and sit and stay for a surprise.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the Phoenicids?

The Phoenicids are a very weak meteor shower that peaks around December 2. Phoenicids, named after the Phoenix constellation, are famous for their erratic behaviour.

When is the best time to see the Phoenicids?

As with most meteor showers, the peak viewing time will be after midnight on December 2nd. Locate yourself under clear, dark skies, far from the glare of city lights, to give yourself the best chance.

Where can I watch the Phoenicids in the U.S.?

Perfect viewing locations are dark-sky parks like those located in Arizona, Nevada, and California. Dark sky national parks and other rural areas are typically the best places to see meteor showers.

How many meteors can I expect to see during the Phoenicids?

Typically, the Phoenicids are a low shower of only a couple meteors per hour at best. Some years will feature a rare outburst, but it is overall a very quiet meteor shower.

See also:

- Previous meteor shower: Andromedid Meteor Shower

- Next meteor shower: December Phi Cassiopeid Meteor Shower

Would you like to receive similar articles by email?