Andromedid Meteor Shower Guide

The Andromedid meteor shower is a small variable rate shower associated with comet 3D/Biela, characterized by occasional outbursts and dim, sluggish meteors. Peak activity in late November with a radiant near Andromeda. Normal rates are low, generally below 2 per hour, but storms in the past have numbered in the thousands. To set expectations, the following sections address timing, visibility, observing tips and the shower’s evolving history.

The Lost Comet

The Andromedid meteor shower, stemming from the periodic comet 3D/Biela, has a fascinating history tied to its break-up, which created a thick meteoroid stream. This event unleashed spectacular Andromedid meteor storms and continues to influence predictions of meteor shower activity today.

Biela’s Demise

First observed in 1772 at the limit of naked‑eye visibility, 3D/Biela was rediscovered on successive returns during the early 1800s, establishing its 6.6‑year period and verifying that it was a regular visitor. By 1846, telescopes revealed two nuclei. Observations in 1852 laid bare the greater distance, suggesting the primary disintegration had occurred in 1842–1843 amid a passage near Jupiter that strained its orbit and structural integrity.

After 1852 both fragments faded and were never again verified, thus giving the object its “lost” status. Its end was not quiet: the disintegration fed the meteoroid complex that later struck Earth.

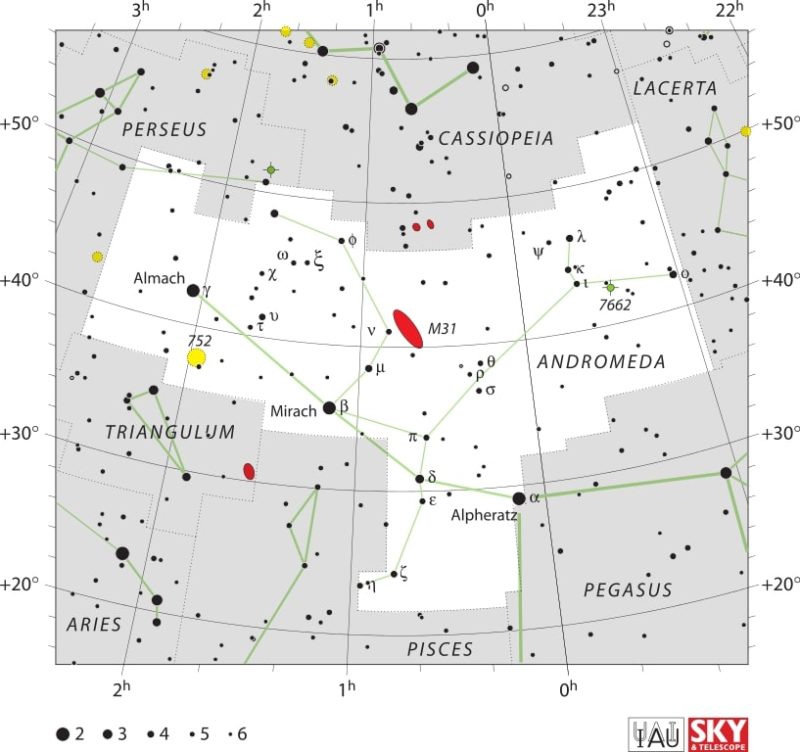

Biela’s death reset shower geometry. Early activity coincided with a radiant in Cassiopeia, but later Andromedid displays drifted into Andromeda as dust swarms migrated under planetary disturbances and radiation pressures.

Celestial Debris

The fragmentation released significant quantities of volatile‑laden grains and centimeter‑sized clasts, composing the Andromedid stream. The Earth slices through this stream when the nodes intersect our orbit, so even minor shifts in inclination, node longitude, and mean anomaly all modulate the rates.

The field’s high phase‑space density following breakup that fueled 19th‑century storms. On November 27, 1872, as many as ~3,000 meteors per hour were observed. 1885 gave us another searing performance. Now the stream is scattered, the shower feeble or wanting in the majority of years since the nineteen hundreds.

A New Shower

Late 18th century observers recorded intense rates from this source. Eventually, accurate orbits connected the shower to 3D/Biela, confirming its parentage and explaining why activity spiked following the comet’s demise.

It is now listed with a radiant in Andromeda and a season of late November to early December, peaking on November 30. Rare outbursts are still possible when the Earth crosses dense, ancient trails.

A Forgotten Spectacle

Once a headliner, the Andromedids generated record storms to compete against the Leonids and later Geminids. Their spectacular Andromedid meteor shower activity has waned through the 20th century, leading most observers to overlook them, but their legacy continues to garner close attention from experts and astronomy enthusiasts alike.

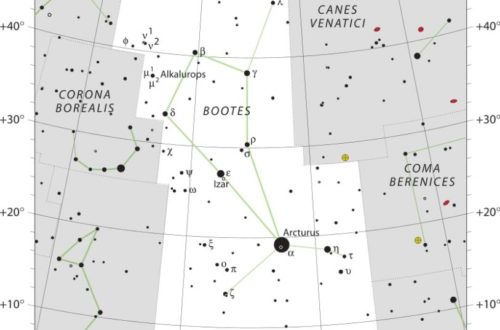

Radiant Point

The current radiant is in the constellation of Andromeda. The radiant shifts throughout the activity period, so meteors appear to emanate from slightly varying locations on different evenings.

Meteor Speed

Andromedid meteors are slow: speed of 18 km/s. Slow entries produce longer, frequently dim, trains from small grains. In contrast with Perseids or Leonids, movement appears slow and easier to tag from sporadics.

Modern Faintness

Today’s rates are low, typically 2 or less meteors per hour. The stream has spread out and become tenuous—an inevitable consequence of planetary perturbations, radiation pressure, and differential precession over hundreds of years.

Take the Andromedids for what they are—a silent, fashionably ancient whisper—deserving of your detailed indulgence.

Viewing Guide

Schedule observations for the Andromedid meteor shower from November 25 to December 5, focusing on the maximum on November 30 and the three nights surrounding it. Prefer moonless, cloud-free windows; even thin cloud or bright moonlight can erase faint Andromedids. Keep expectations low—this is a shallow yet legendary creek with occasional rapids.

Find Darkness

Find a dark‑sky location far away from city lights. Faint Andromedid streaks disappear in skyglow that raises the background brightness and mutes contrast. Rural fields, coastal headlands and high‑altitude pullouts—all often work if the horizon is clear.

Light pollution is the primary failure mode here. Even LED streetlights kilometers away can reduce your limiting magnitude by 1–2 mags, sufficient to obscure most Andromedids. A Bortle 3–4 site is realistic.

Leveraging dark‑sky maps and light‑pollution overlays helps to select good locations. Certified astronomical parks provide predictable access and lighting regulations.

Allow Time

Block an hour at minimum, longer if possible. Low hourly rates imply stats get better with time on target, not quick peeks.

Get there early, hang around past midnight into pre‑dawn where the radiant climbs. Activity is clumpy—silent stretches can turn to frantic bursts—so patience counts.

Pack a lounge chair or pad, warm layers, hat, gloves and a thermos. Bring along a dew cover and windbreak if it’s damp or breezy.

Use Your Eyes

Go with the naked‑eye—meteors are wide‑field transients, and optics reduce your sky portion. Lie flat on your back to maximize field of view—the more sky you see, the better your odds.

Look widely but favor attention toward the Andromeda radiant. A brighter glow enhances the view, but meteors can shine through all. Rotate to refresh sensitivity.

Allow eyes to adjust 20–30 minutes at least. Leave your phone inside or employ a dim red light exclusively.

View with buddies to expand coverage and callouts. It depends on the shower and the season, so consider moon phase, weather, and your local horizon every time.

Conclusion

A silent Andromedid meteor shower may seem insignificant, but it bears enduring remembrance. Every filament of 3D/Biela dust connects us to those who recorded 19th-century storm outbursts. Even one meteor is a bridge that turns cold numbers into lived time. That’s why I stop after each trace and inquire what it dredged up—wonder, astonishment, or the mere requirement to escape our stress-filled lives.

Need more depth? Review ancient outburst reports, research trail maps, and establish a basic watch plan for following windows. Got notes or shots? Share them!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Andromedid meteor shower?

The Andromedids, a feeble meteor shower linked to Comet 3D/Biela, exhibit variable activity due to chaotic dust streams, leading to occasional bursts of activity, despite generally low peak rates.

When and where should I look to see the Andromedids?

Watch for the Andromedids meteor shower activity in late November to early December. Face in the direction of the constellation Andromeda, but monitor a large portion of the sky for these spectacular meteors.

How many meteors can I expect per hour?

Most years yield few meteors, often less than 2 per hour, with the possibility of rare outbursts that can be unpredictable. Adjust your expectations and savor the sky.

Why is the Andromedid meteor shower so unpredictable?

The dust trails from the divided, ‘lost’ comet (3D/Biela) contribute to the Andromedid meteor shower activity, as gravitational nudges and solar radiation disperse particles, making timing and intensity difficult to predict.

Do I need special equipment to watch?

No. Use your eyes to observe the night sky during the Andromedid meteor shower activity. Grab a lounge chair, bundle up, and give your eyes 20-30 minutes for dark adaptation.

Is the Andromedid meteor shower safe to observe?

Yes. Meteor watching, especially during the Andromedid meteor shower activity, is harmless. Safeguard your night vision, be alert, and scout local weather to minimize exposure.

See also:

- Previous meteor shower: November Orionid Meteor Shower

- Next meteor shower: Phoenicid Meteor Shower

Would you like to receive similar articles by email?